The article asks whether Asian health providers should look at mergers and acquisitions in order to stay competitive and avoid being ‘eaten’ by larger players. This should be a pressing question for the C-suite in healthcare as well as private equity investors interested in buying out healthcare companies. My basic premise is that companies can better strategize their next move if they are closely attuned to their industry’s lifecycle and their position within this industry.

A bird’s eye view of the global healthcare landscape reveals a market in consolidation and the implications for Asia are well worth considering. In 2016, healthcare M&A activity worldwide topped ~$320B. With 169 deals valued at ~$29B, Asia accounted for 9 per cent of the global pie. For some healthcare players, the endgame might be more apparent than others: If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu—or worse still, on your way out.

Back in 2008, Chinese medical device manufacturer Shenzhen Goldway Industrial found itself on the menu, when Phillips snapped it up in a bid to solidify its place in the patient monitoring market. Fast forward a couple of years and Asia-based providers are increasingly ‘at the table’ making their own cross-border bids. In January 2017, Indian pharmaceutical player Zydus Cadila made inroads into the US specialty pharma market with the acquisition of California-based Sentynl Therapeutics, a company that acquires, develops and commercialises prescription products in the pain management segment. Transactions like these have followed on the heels of similar M&A activity in 2016. Last February, Indian pharmaceutical player Cipla sealed the deal on two US-based companies, InvaGen Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Exelan Pharmaceuticals Inc. Later, in April, Singapore-based Luye Medicals Group acquired Australia’s Healthe Care, vaulting into position as one of the largest private medical groups in the region.

With an ‘eat or be eaten’ narrative at play, should Asian health providers increasingly look to the acquisitions bandwagon to stay competitive? Whether through local or cross-border deals, the question is a pressing one—both for the C-suite in healthcare and private equity investors interested in profiting from consolidations and ‘rolling up’ businesses in this space.

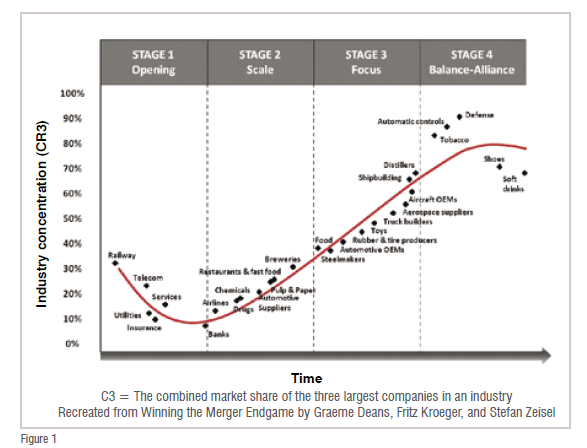

According to the merger endgames theory posited by A.T. Kearney researchers circa 1990, the answer depends on where a particular industry falls in a four-stage consolidation lifecycle. The theory—which is based on an analysis of ~25,000 companies across 24 industries globally—suggests that all industries will journey through the same four stages over a ~25 year period. The companies that fare well in the long-term are reportedly the ones that take a proactive role in driving their industry’s consolidation—the so-called endgame.

The idea is simple. If it is possible to understand the defining traits of each stage in the consolidation lifecycle, a business should undertake every major strategic and operational move in line with their place in a particular industry and the industry’s stage in the overall consolidation trajectory.

This sounds promising in theory, but what does it mean?

Stage 1: An industry is said to ‘open’ with a single start-up or a monopoly resulting from deregulation or privatisation. Initially, industry concentration stands at 100 per cent but as competitors make swift inroads, the market quickly becomes fragmented and the combined share of the three largest players drops to between 10–30 per cent. Players at this initial stage are focused on making inroads, with no real rationale for consolidation.

Stage 2: With the passage of time, players in the industry switch towards building scale and the Top Three come to hold 15–45 per cent of the market. This is a stage of rapid consolidation as larger players absorb smaller targets in their effort to create ‘empires’.

Stage 3: By this stage, players in the industry are focused on developing their core business and outpacing the competition, with the Top Three claiming 35 per cent–70 per cent of the market. Unlike the previous phase when larger companies acquired weaker targets, Stage 3 is all about mega deals and large-scale consolidation plays—in essence, the emphasis is on the merger of equals.

Stage 4: During the balance and alliance stage, the Top Three companies control 70 per cent–90 per cent of the market. This is a stage when further consolidation is either limited or non-existent, whether due to antitrust concerns or industry complexity. Instead, companies operating in these industries must defend their leading positions.

Application of the Consolidation Lifecycle

Within the global healthcare landscape, many providers are focused on a medley of consolidation, convergence and connectivity. The concern is that consolidation decisions don’t always pan out as planned, partly due to poor timing. For Asian healthcare providers, the need of the hour is to build strategy around the stage of the industry in which they operate. What might it look like if the consolidation lifecycle was applied to some of these players?

Stage 1: Regenerative Medicine in Japan

In Japan, regenerative therapies are a good example of a Stage 1 industry, owing to a new legal framework for cell-based and tissue-based therapies that went into effect in November 2014—expediting the development and conditional approval of products that demonstrate safety and probable efficacy. Japanese corporations such as Cyberdyne and Healios K.K. are increasingly investigating opportunities to bring regenerative therapies to market, even as foreign companies—like Australian regenerative medicine business Mesoblast—look at more partnership deals in Japan.

According to the consolidation lifecycle, the right move for companies in Stage 1 industries is to aggressively defend their first-mover advantage by building scale, developing a global footprint and protecting proprietary technology and ideas. The recommendation for Stage 1 companies is to focus more on earning revenue and amassing market share, particularly before competitors encroach upon the opportunity. In a space soon to be flooded by CMOs, CROs, biotech and pharma companies, the need of the hour is for Japanese businesses to grow within parameters that safeguard proprietary technology. Healios is an example of a Japanese company that seems to be doing this right. In January 2016, the company announced a partnership with US-based Athersys, aimed at the development and commercialisation of novel cell therapy treatments. The partnership includes MultiStem, a proprietary, patented off-the-shelf stem cell therapy developed by Athersys for multiple disease indications. If the consolidation lifecycle is to be believed, it is still too early for players in this stage to consider acquisitive activity as a viable strategic move.

Stage 2: Pharmaceuticals Sector in Japan, China and India

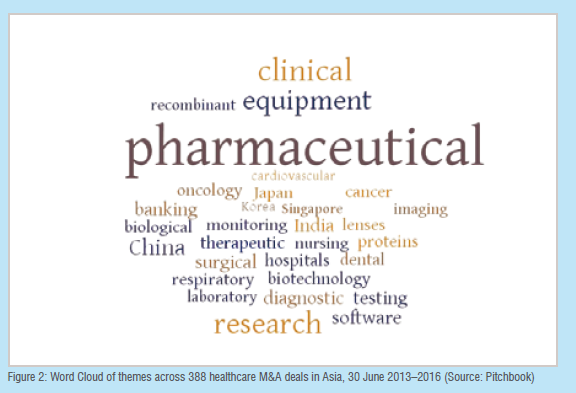

A sampling of recent deal activity in Asia suggests that the pharmaceuticals sector is a good example of a Stage 2 industry where players have been focused on building scale. In the three years leading up to 30 June 2016, ~388 healthcare deals transpired in Asia. Amongst these, ~125 deals were in the pharmaceuticals and biotechnology space—with ~70 per cent of acquisitive activity involving companies based in Japan, China and India.

Mergers and acquisitions have long been underway in Japan’s Big Pharma market; with much large-scale domestic consolidation having already taken place in the past decade involving companies like Astellas and Takeda. Despite this wave of M&A, Japan’s pharma sector is still largely fragmented and there remain further opportunities for deal-making to expand both R&D investments and end-market reach.

Aside from overseas deals, large Indian pharma companies like Torrent Pharmaceuticals have been busy swallowing up smaller players. In Torrent’s case, these acquisitions have been a means of quickly enhancing their standing as a manufacturer of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) for regulated markets.

In China, most of the deal activity over the past three years has involved domestic players around Chinese herbals and natural medicine, biopharmaceuticals and other manufacturers of capsules/tablets. In May 2016, vitamin-maker Blackmores acquired Global Therapeutics, Australia’s top Chinese herbal medicine retailer, in a bid to enhance its product push into Asia and deepen its understanding of the Chinese market.

In this sense, a Stage 2 industry is one that has found its bearings—front-runners in such industries typically enjoy a stable income stream, diverse end-markets, entrenched customer relationships and a clear value proposition. At this point, it makes sense to build scale. As such, Stage 2 is typically characterised by larger players regularly absorbing smaller targets in an effort to create empires. On the flip side, companies that opt to sit out the M&A wave can grow increasingly vulnerable to ‘being eaten’. Achieving a finely calibrated fit in terms of acquisitions may well be pivotal for businesses that do not wish to be overtaken in a Stage 2 industry.

Stage 3: In-Vitro Diagnostics (IVD) Market in China

Globally, the IVD industry has been rather deal-oriented with ~240 acquisitions between 2012 and October 2015. With in-vitro diagnostics influencing over 60 per cent of clinical decision-making, this is a market that appears to be switching from Stage 2 to Stage 3 in China—with foreign players driving the endgame rather than homegrown companies. International companies currently account for ~75 per cent of the Chinese market; with giants like Roche (~20 per cent), Abbott (~12 per cent) and Siemens (~10 per cent) dominating the space. Homegrown players like Mindray Medical, DaAn Gene, Fosun Diagnostics and Shanghai Kehua Bio-Engineering comprise the rest of the market.

For players entering Stage 3, the strategic priority is to enhance their core business and outpace the competition via large-scale consolidation plays. The goal is no longer the acquisition of smaller targets but mergers of equals. Over the past 2 years, Roche in particular has embarked on a string of acquisitions in order to ensure that the company has an end-to-end value proposition that meets the needs of customers in the clinical sequencing arena. To improve sample preparation, Roche acquired Kapa Biosystems, Lumora, AbVitro, and MilliSect. It also acquired nanopore sequencing firm Genia and launched collaborations with sequencing tech firms like Stratos. Roche also took on Bina Technologies for its informatics, to generate actionable data. In China itself, Roche invested in a new diagnostics equipment manufacturing facility in 2014 to respond better to the local market. In future, Roche is an example of a company that is likely to shift from the acquisition of smaller targets towards large-scale consolidation plays. By comparison, it would appear that homegrown Chinese players in the IVD space have already lost the merger endgame.

Stage 4: Private Hospitals in Singapore

Singapore’s private hospital space is on the cusp of transition from Stage 3 to Stage 4. While large companies operating in Stage 3 of the industry lifecycle tend to focus on outpacing the competition via large-scale consolidation plays, such players eventually transition into Stage 4 ‘Grandmasters’ whose priority it is to defend their leading positions.

IHH Healthcare Berhad—the 2012 IPO-ed offspring of Singapore’s Parkway and Malaysia’s Pantai—is a solid example of a merger of equals that is pushing Singapore’s private hospital market towards Stage 4. In 2012, IHH alone commanded ~44 per cent of licensed beds and ~70 per cent of revenues across Singapore. With ~10,000 licensed beds in 52 hospitals across 10 countries and a market value of ~$14.2B in 2016, IHH also tops the region’s healthcare providers in market value.

IHH still appears focused on acquisitions in the medium term. In 2015, the company picked up two hospitals in India—Continental and Global. However, in future, it is likely that such acquisitive activity will fast become untenable due to antitrust concerns. In 2015, The Competition Commission of Singapore blocked IHH’s proposed acquisition of RadLink-Asia, a provider of diagnostic imaging and radiography services in Singapore. Consequently, during this stage, alliances and spin-offs may become more attractive strategies. Ultimately, companies that lead in Stage 4 industries have the potential to be successful for a long time depending on how they handle their position.

So What?

Ultimately, the merger endgames theory or consolidation lifecycle has its limitations in terms of the precision with which it can explain an industry’s trajectory over time and the behaviour of companies within these industries. The real value of the consolidation lifecycle, however, is as one of several frameworks for strategic thinking. By studying the cycles through which industries pass, learning to identify where in the cycle their industry currently stands, and understanding the anticipated evolution of consolidation moving forward, Asian healthcare players can better determine which organisational changes to make, when to make them and how to develop and deploy the most feasible acquisition strategies. Health conglomerates can also leverage this knowledge in order to optimise their aggregate portfolio of subsidiaries and business units across the different endgame stages. Not every player can lead the consolidation endgame but there is much to be learned by tracking the progress of Endgame winners, like Roche and IHH Healthcare.

References:

01. Pitchbook Data, 2016–17

02. Healthcare Business, 2008, https://www.dotmed.com/news/story/5784

03. Zydus Cadila Press Release, 2017, https://zyduscadila.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Press-Release-Sentnyl.pdf

04. Cipla Press Release, 2016, http://www.cipla.com/uploads/mediakit/1455769166_Press%20Release%20-%20InvaGen%20Final.pdf

05. ACN Newswire, 2016, https://www.acnnewswire.com/press-release/english/29618/singapore-based-luye-medical-group-completes-acquisition-of-healthe-care,-australia's-third-largest-private-healthcare-group

06. Graeme K. Dean,s Fritz Kroger, and Stefan Zeisel, ‘The Consolidation Curve’, Harvard Business Review, December 2002 Issue https://hbr.org/2002/12/the-consolidation-curve and Winning the Merger Endgame: A Playbook for Profiting from Consolidation, McGraw Hill, 2003

07. RepliCel, http://replicel.com/recent_coverage/japans-take-on-regenerative-medicine-early-commercialization-early-reimbursement/

08. Japan Times, 2015, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/09/03/national/science-health/regenerative-medicine-get-boost-deregulation-japan/#.V9EC7vl95CA

09. Athersys Press Release, 2016, http://www.athersys.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=949491

10. Pitchbook Data, June 2013–16

11. http://www.deallusconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/presentations/is-the-pharmaceutical-industry-ready-for-increasing-competition-in-japan.pdf

12. Indian Express, 2016, http://indianexpress.com/article/business/companies/torrent-pharma-to-acquire-api-manufacturing-unit-of-glochem-industries-ltd-2886296/

13. The Australian, 2016, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/companies/vitamin-maker-blackmores-buys-into-chinese-herbal-medicine/news-story/626b75b5bd304c066cb8f294a4d5bc83

14. Kalorama, 2015, http://www.kaloramainformation.com/Mergers-Acquisitions-IVD-9368424/

15. DBS Group Research, 2015, https://www.dbs.com/insights/media/China%20Healthcare%20Sector.pdf

16. Genome Web, 2016, https://www.genomeweb.com/molecular-diagnostics/aggressive-acquisition-strategy-fills-out-roches-pipeline-dx-tests-and

17. Credit Suisse, IHH Healthcare, 22 August 2012

18. IHH Healthcare Website

19. VCC Circle, 2015, http://www.vccircle.com/news/healthcare-services/2015/08/28/malaysias-ihh-buy-734-global-hospitals-194m

20. Competition Commission Singapore Media Release, 2015